Humanitarian Impacts

CATASTROPHIC HARM

Nuclear weapons are the most destructive, inhumane and indiscriminate weapons ever created. Both in the scale of the devastation they cause, and in their uniquely persistent, spreading, genetically damaging radioactive fallout, they are unlike any other weapons. A single nuclear bomb detonated over a large city could kill millions of people. The use of tens or hundreds of nuclear bombs would disrupt the global climate, causing widespread famine.

USE, TESTING AND PRODUCTION

Nuclear weapons have been used twice in warfare – on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. More than 210,000 innocent civilians died, while many more suffered acute injuries. Even if a nuclear weapon were never again exploded over a city, there are intolerable effects from the production, testing and deployment of nuclear arsenals that are experienced as an ongoing personal and community catastrophe by many people around the globe. This must inform and motivate efforts to eliminate these weapons.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings →

The legacy of nuclear testing →

Diversion of public resources →

IMMEDIATE AND WIDER EFFECTS

Nuclear weapons are unique in their destructive power and the threat they pose to the environment and human survival. They release vast amounts of energy in the form of blast, heat and radiation. No adequate humanitarian response is possible. In addition to causing tens of millions of immediate deaths, a regional nuclear war involving around 100 Hiroshima-sized weapons would disrupt the global climate and agricultural production so severely that more than a billion people would be at risk of famine.

Climate disruption and famine →

Modelling the effects on cities →

IMPACT ON AUSTRALIA

For many Australians, nuclear weapons are not a distant, abstract threat, but a lived reality – a persistent source of pain and suffering, of contamination and dislocation. Indigenous communities, long marginalised and mistreated in Australia, bear the brunt of this ongoing scourge.

From 1952 to 1963, the British government, with the active participation of the Australian government, conducted 12 major nuclear test explosions and up to 600 so-called “minor trials” in the South Australian outback and off the West Australian coast. Radioactive contamination from the tests was detected across much of the continent. At the time and for decades after, the authorities denied, ignored and covered up the health dangers.

Little was done to protect the 16,000 or so test site workers, and even less to protect nearby Indigenous communities. Today, survivors suffer from higher rates of cancer than the general population due to their exposure to radiation. Only a few have ever been compensated. Much of the traditional land used for the blasts remains off limits.

YAMI LESTER

Yankunytjatjara elder and nuclear test survivor (1942-2017)

Yami Lester was 10 years old when the “Totem 1” nuclear test was conducted near his home in 1953. His eyes stung as a result, and four years later he lost all sight. Since the 1980s he has been a leading advocate on behalf of communities affected by the tests.

“It was in the morning, around seven. I was just playing with the other kids. That’s when the bomb went off. I remember the noise, it was a strange noise, not loud, not like anything I’d ever heard before. The earth shook at the same time; we could feel the whole place move. We didn’t see anything, though. Us kids had no idea what it was. I just kept playing. It wasn’t long after that a black smoke came through. A strange black smoke, it was shiny and oily. A few hours later we all got crook, every one of us. We were all vomiting; we had diarrhoea, skin rashes and sore eyes. I had really sore eyes. They were so sore I couldn’t open them for two or three weeks. Some of the older people, they died. They were too weak to survive all of the sickness. The closest clinic was 400 miles away.”

AVON HUDSON

Whistleblower and nuclear test veteran

Avon Hudson was a serviceman at Maralinga during some of the disastrous “minor trials” of 1958 to 1962. With his intimate first-hand knowledge of the effects of radiation on human health, he is now a passionate campaigner for a nuclear-weapon-free world.

“We were innocent – lambs to the slaughter – and have been treated with contempt by Australian governments of both political persuasions trying to sweep their tarnished history under the carpet. We have suffered; for many of our friends, life was cruelly taken away or changed forever by an unseen and largely unknown foe – ionising radiation. We were naive and trusting of our government. Now they are waiting for us to die. This is an uncomfortable history for many a politician, because it cannot be spoken of in the abstract – families are still suffering. At the time of the tests, the Australian public was deliberately and ruthlessly kept in the dark concerning the real effects of the atomic bomb explosions and the so-called ‘minor trials’.”

SUE COLEMAN-HASELDINE

Kokatha-Mirning woman and nuclear test survivor

Sue Coleman-Haseldine was born in 1951 at the Koonibba mission near Maralinga, a site of British nuclear testing. She won the South Australian premier’s award for excellence in Indigenous leadership in 2007 for her work as an activist, cultural teacher and environmental defender.

“I was about three when it happened. The old people used to talk about the Nullarbor dust storm, which really wasn’t a dust storm at all. It must have been the fallout from Maralinga. We’ve had thyroid problems in the family, and it’s not just us, it’s the whole of the west coast of South Australia. We’ve had quite a lot of problems like that, health-wise. And when someone says somebody’s just died, you ask what from and it’s always cancer, cancer, cancer. But as we all know, nobody can prove that the radiation caused the cancer. People have put in for compensation, but because there’s no proof that the illnesses stem from the explosions, there is none.”

YVONNE MARGARULA

Mirarr Senior Traditional Owner

Yvonne Margarula’s tireless work to protect her country is world renowned. In the 1990s she led the successful campaign to stop a second uranium mine, Jabiluka, from being built on Mirarr land. Australian uranium has been used to produce British and US nuclear weapons, and the Australian government continues to export uranium to nuclear-armed nations, contributing to global proliferation dangers.

Yvonne’s late father, Toby Gangale, outlined his concerns about the Ranger uranium mine in 1978: “I don’t like the mine you see. Very dangerous. What if they make an atom bomb or something? Very dangerous: the same thing as they did in Japan. Flat. All the big houses, all the big buildings. Very dangerous. That’s why we’re worried.” The Ranger mine continues to operate today, despite Mirarr concerns.

“My name is Yvonne Margarula. I am the Senior Traditional Owner of Mirarr country in Kakadu, Australia. In the 1970s the government and mining company came here and forced the Ranger uranium mine on us. All Bininj were against the mine, but we could not stop it. Our land has suffered. We lost billabongs and rivers. Often we are worried because of the mine. We use the water for fishing, swimming and drinking. In my heart I feel that things would be better if there were no mining here. But we Mirarr are strong and will use the opportunities to create a better future.”

JUNKO MORIMOTO

Artist, author and atomic bomb survivor (1932-2017)

Junko Morimoto is a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. She migrated to Australia from Japan in 1982. Her picture books are widely read by schoolchildren throughout the world and include the autobiographical My Hiroshima.

“My life was quite peaceful before the atomic bombing. I was living happily. I enjoyed day-to-day life, doing things like learning to dance and playing with my friends. At the time, I believed my life would continue like this forever. I was 13 years old. While talking to my sister, I heard a loud boom! and we were surrounded by an incredible light and heatwave. In the moments soon after, we were hit with an earth-shattering roar. It got really, really dark as if day had suddenly turned into night. We were in a pile of rubble that had once been our home. Surrounded by screams, it was as if I were in hell. There was a child screaming, trying to wake her dead mother.”

HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVE TIMELINE

The catastrophic, persistent effects of nuclear weapons on our health, societies and the environment must be at the centre of all public and diplomatic discussions about nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. This is the basic principle underpinning what has become known as the Humanitarian Initiative.

From 2010, governments, the international Red Cross and Red Crescent movement, various United Nations agencies, and non-government organizations began working together to reframe the debate on nuclear weapons – giving rise to the groundbreaking UN process to negotiate a global prohibition on nuclear weapons.

ICAN was a central part of this initiative from its beginning, serving as the civil society partner for three major intergovernmental conferences on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, and at every opportunity encouraging governments to work with urgency to achieve the ban. Here are some of the defining moments.

TIMELINE

MAY 2010: NON-PROLIFERATION TREATY CONFERENCE

In the final document adopted by consensus at the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference in 2010, parties to the treaty express their “deep concern at the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons”. This gives impetus to future statements and conferences on the subject. Click here for ICAN’s report.

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Jody Williams speaks at an ICAN side event at the conference.

NOVEMBER 2011: RED CROSS RESOLUTION

The international Red Cross and Red Crescent movement – the largest humanitarian organization in the world – adopts a landmark resolution appealing to all nations to negotiate a “legally binding international agreement” to prohibit and completely eliminate nuclear weapons. Nuclear disarmament becomes a top Red Cross priority.

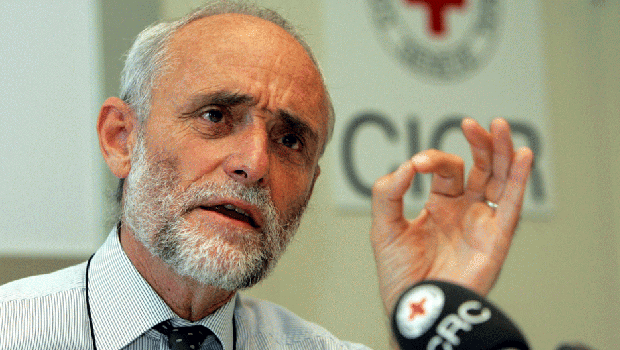

Red Cross leader Jakob Kellenberger calls for an end to “the era of nuclear weapons”.

MAY 2012: FIRST HUMANITARIAN STATEMENT

On behalf of 16 nations, Switzerland delivers the first in a series of joint statements on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, urging all nations to “intensify their efforts to outlaw nuclear weapons”. Support for this humanitarian call grows with each new statement. Eventually, 159 nations – four-fifths of all UN members – sign on.

The NPT meeting in Vienna in 2012 at which the first humanitarian statement is delivered.

MARCH 2013: OSLO CONFERENCE

Eager to strengthen the evidence base for prohibiting and eliminating nuclear weapons, Norway hosts the first-ever intergovernmental conference on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, attended by 128 nations. Relief agencies declare that they would be powerless to respond meaningfully in the aftermath of a nuclear attack.

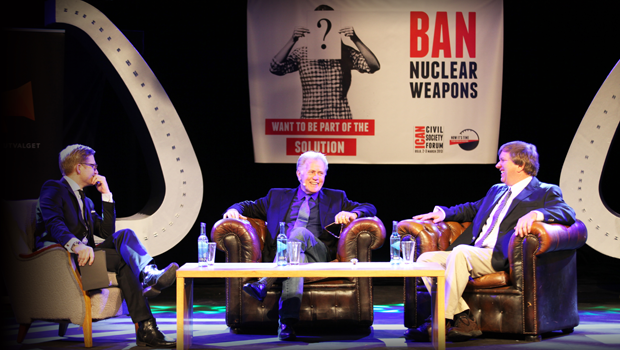

Actor and activist Martin Sheen addresses an ICAN forum ahead of the Oslo conference.

February 2014: NAYARIT CONFERENCE

Mexico hosts the second humanitarian impact conference, in Nayarit, with 146 nations present. The chair calls for the launch of a “diplomatic process” to negotiate a “legally binding instrument” to prohibit nuclear weapons – a necessary precondition, he says, for achieving elimination. He declares the conference “a point of no return”.

ICAN delivers a video statement at the Nayarit conference.

DECEMBER 2014: VIENNA CONFERENCE

A record 158 nations participate in the third conference on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, in Vienna, which concludes with a pledge to cooperate in efforts to “fill the legal gap” in the international regime governing nuclear weapons. Within months, 127 nations endorse the document, known as the Humanitarian Pledge.

Six hundred ICAN campaigners gather in Vienna ahead of the conference.

AUGUST 2015: HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI ANNIVERSARIES

Organizations throughout the world hold events on 6 and 9 August 2015 to mark 70 years since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which claimed more than a quarter of a million lives. ICAN urges governments to fulfil the Humanitarian Pledge by launching a process to negotiate a global ban on nuclear weapons.

AUGUST 2016: UN WORKING GROUP IN GENEVA

A special UN working group on nuclear disarmament meets in Geneva in February, May and August 2016 to discuss new legal measures to achieve a nuclear-weapon-free world. It recommends the negotiation of a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons – a decision that the Red Cross describes as having “potentially historic implications”.

Governments vote overwhelmingly in favour of adopting the working group’s report.

DECEMBER 2016: UN GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION

The United Nations General Assembly adopts a landmark resolution to convene a conference in 2017 to negotiate “a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination”. The decision heralds an end to two decades of paralysis in multilateral nuclear disarmament efforts.

The First Committee of the General Assembly adopts the resolution on 27 October 2016.

JULY 2017: NUCLEAR WEAPON BAN TREATY ADOPTED

Following a decade of advocacy by ICAN and its partners, and weeks of negotiations at the UN headquarters in New York, an overwhelming majority of the world’s nations vote in favour of adopting a landmark global agreement to ban nuclear weapons, known officially as the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Elayne Whyte Gomez, who chaired the negotiations, celebrates as the treaty is adopted.